The rise of authoritarianism in Turkey may provide a chilling look into America’s future.

By: Daniel McElroy

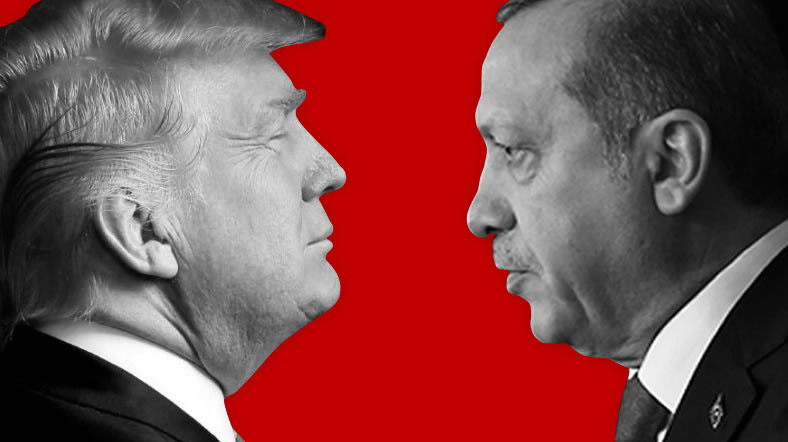

Many Americans have spent the past several months watching and reacting to the nascent Trump administration, mobilizing in resistance to measures such as the Muslim ban, mass deportations, and an assault on transgender rights. Thus, much attention—when not focused on Putin and Russia—has been largely focused inward. And while Mr. Trump’s reading of the teleprompter and condolences at last week’s joint session of Congress elicited much fawning praise for his “presidential” performance, content and policies notwithstanding, one might do well to look at other examples of leaders who have similarly used the language of populism, scapegoating of foreigners and minorities, and the accoutrements of high office to gain and shore up power. Particularly instructive due to the number of similarities, and perhaps a stark warning for what the future could hold for America, is President Erdoğan of Turkey.

President Erdoğan made international headlines last week accusing Germany of “Nazi practices” for blocking political rallies even as he attempts to increase his own power through referendum at home. These actions echo some of Mr. Trump’s similar accusations leveled against the U.S. media and intelligence community, but the similarities between Trump and Erdoğan run much deeper and point to broad, shared ideological strains arising throughout the West over the past several years.

Seen as a man of the people and elected partially as a response to a floundering economy, Erdoğan became Prime Minister of Turkey in 2003. He served three terms and then, in 2014, became the country’s first elected (rather than appointed) President. He spent the days leading up to his election making statements widely perceived as anti-Semitic in an attempt to rally support from Turkish Muslims, the vast majority of voters in the country, and like Trump’s majority appeals—similarly polarizing, obversely anti-Muslim—these were widely decried as reckless and internationally alienating. Nonetheless, voters in both countries were drawn to these men and their scapegoating of vulnerable minorities due to widespread disillusionment with leaders and economies that they felt had left them behind long ago. Of note, however, neither Trump nor Erdoğan received the majority of the popular vote in their respective countries.

Once in office, both men have continued resorting to outlandish rhetoric and name calling in order to centralize power, continuing attacks on marginalized groups, and as an Islamist in a Muslim-majority country, Erdoğan’s rhetoric mirrors Trump’s appeals to the American Christian far-right. For years, Turkey claimed goodwill toward its neighbors by tolerating a large undocumented Armenian population, but Erdoğan’s patience with such a policy ended when the U.S. and EU tried to officially recognize the Armenian Genocide in 2010 and 2015, respectively. When it looked like the European Parliament would vote to recognize the genocide, Erdoğan threatened mass deportations. And his government did carry out mass deportations of Syrian refugees in 2016, leading to chilling accounts of families split apart in the same way we’re hearing about now in America. Erdoğan called for and built his own border wall to keep refugees out, and the result—perhaps a chilling portent of what could come of Mr. Trump’s border wall should it ever be built—has been so many documented beatings and shootings that the area at the wall has been called a “death strip.” A familiar tactic of alternative facts and misinformation was used to cover up and distract, while the government maintained that it had an “open-door policy” for Syrian refugees throughout.

Scapegoating is a widely used tool in shoring up authoritarian power, and in both the U.S. and Turkey under these leaders the political utility of ethnic minorities outweighs their basic human rights. Aldous Huxley wrote of these techniques back in 1958 in Brave New World Revisited:

While Mr. Trump has capitalized on invented terrorist attacks—both at home and abroad—to justify bigoted remarks and policies such as the Muslim ban and his deportation orders, Erdoğan provides an example of which further ends that kind of rhetoric can be employed to reach. Last month, calling his opponents “terrorists” and comparing them to those involved in the attempted 2016 coup, he set a referendum for April 16th which would amend the constitution to broaden the powers of the presidential office and expand his authoritarian control.

Meanwhile, as resistance mounts to Mr. Trump’s policies and deflection is necessary from investigation into potential connections to Russia, his assault on journalism continues to intensify, marked by his usual tactic of the repeated catchphrase “fake news” and the targeting individual organizations and journalists, which laid the groundwork for The White House to bar major publications from press events.

Here again though, Mr. Erdoğan is much farther down the path and perhaps offers a glimpse into America’s future. Erdoğan has been going after individual journalists and newspaper editors for years, accusing them publicly of treason for speaking out against him. When two editors from the Cumhuriyet newspaper were arrested in 2015, a court ordered their release but Erdoğan simply refused to yield and kept them in prison. A year later, he utilized the coup attempt to call for a state of emergency, and following a suicide bombing in Ankara, seized the moment to call for the definition of “terrorist: to be expanded to include journalists and politicians. James Madison spoke of the “favorable emergency,” an oft-used practice by which would-be tyrants work to dismantle democratic institutions as they stress the need for centralized control, and Erdoğan employed this in full force. Arrest warrants for over 100 journalists were issued and 102 media outlets blocked, and according to the Committee for the Protection of Journalists, Turkey now jails more journalists than any other country.

In January, The Voice Project received a letter from one of these journalists, Sedat Laçiner, who is also a well known international politics and anti-terrorism scholar, university administrator, and author. He has now been detained for over seven months, and has yet to be charged with any crime or to have access to his lawyer.

From: Sedat Laçiner

Date: Mon, Jan 2, 2017 at 3:35 PM

Subject: letter from Turkish prison

Dear Sir/ Madam,

I’m one of the jailed academics and writers in Turkey. I’ve been in a Turkish prison (Canakkale) for more than 5 months without an indictment. More than 40 thousands of people, including academics, judges, lawyers, journalists, teachers and the members of Turkish Supreme Court were arrested after the 15 July Coup Attempt. All these jailed people are accused of supporting the coup-attempt. More than 100 thousands of civil servants were fired without any proof and legal process.

The coup attempt has been abused by Erdoğan rule in order to curtail the authoritarian essence.

Similarly I was accused of supporting the coup without any evidence and I was arrested on 20 July 2016 in Canakkale. I cannot reach my lawyer and I have been under dreadful prison conditions.

The Turkish Attorney declared my file “secret” and refuses to give any details of the accusations as it is the case in thousands of files after 15 July 2016.

My only fault is my opinions. I opposed the Syrian and the Kurdish policies of the Erdoğan rule. I’ve also strongly criticized the government’s authoritarian and Islamist policies. Turkey has always been part of Europe and it should be a true member of Europe. I’m afraid the government has making efforts to deviate Turkey’s western direction.

I’ve never been part of any illegal organization or network. I am a professor of International politics and an expert on combatting terrorism. I am author of 26 books and numerous articles. I graduated from Sheffield University (UK) with a MA degree and King’s College London with a PhD degree. I wrote for daily Star (Istanbul), Internethaber and Haberdar news sites.

I have no idea when I could see a judge. My life and my family are under deathly risks and we need your support. Please help us.

Yours,

Prof. Dr. Sedat Laçiner

Canakkale E Type Closed Prison

Canakkale – Turkey

It is crucial to acknowledge how quickly and under what circumstances Erdoğan’s decrees have progressed to the level of arbitrary mass imprisonments. Action against journalists began ramping up in November 2015, as Erdoğan’s party won a landslide election victory that gave it single-party control over the Turkish government. Even with that major boost in power, however, Erdoğan and his allies claimed a significant threat from opposition and an ongoing war with the Kurdistan Workers’ Party in the eastern part of the country loomed large. At that time, short term detentions and warnings were common, but just six months later, by utilizing the state of emergency tactic, arrests had became the norm and still are.

Sedat Laçiner continues to seek due process, but has yet to receive any indication that a trial or release will happen any time soon. Laçiner is a single individual caught in the middle of Erdoğan’s political machinations, and his personal account perhaps affords a chilling look into what could happen in America. Several years ago, few would have imagined that Turkey, a country on track for EU membership, could end up in its current position, or that a journalist like Laçiner—and so many journalists, academics, novelist, singers and artists—could find themselves in prison.

We must not assume that Mr. Trump’s varied assaults on American constitutional rights are limited to their current scope. The tactics employed by him and Steve Bannon have very often been used to prepare the ground for future battles, ones intended to carefully dismantle democratic institutions and constitutional protections of basic human rights. Resistance at this particular moment is essential. Currently, Republican-led state legislatures in over a third of the states in the U.S. are trying to limit Americans’ right to free speech, and protest as bills have been introduced that seek to criminalize demonstrations of all types. (For more details on how to resist this legislation, see the tracking tools here.)

And finally, we must not forget that strength in numbers is not limited by borders. An assault on journalistic or other freedoms anywhere is an assault on those freedoms everywhere, so we must make it our mission to stand against oppression on all fronts, applying both domestic and international pressure to authoritarians. We need to do this for others, and they for us. To that end, we urge you to take action and speak out for Sedat Laçiner here, as well as the other imprisoned Turkish artists and activists we have ongoing campaigns for, including Atilla Tas, Zehra Dogan, and Nûdem Durak. In this contentious time, we must continue learning from each other and standing up for one another, no matter the distance and no matter the borders. Together, perhaps, we will we have the power to perserve democratic governance and freedom of expression for posterity.