In recent months, Iran’s Revolutionary Courts have sentenced one activist to 14 years for charges which included listening to protest songs, two artists to a combined 20 years in prison for their work, and four other activists have been sentenced to a combined 31 years. While these harsh sentences have been met with international criticism while the country’s president Hassan Rouhani has been working to normalize relations with the west, his silence on the matter has shown the firm grasp of the country’s Supreme Leader on its affairs.

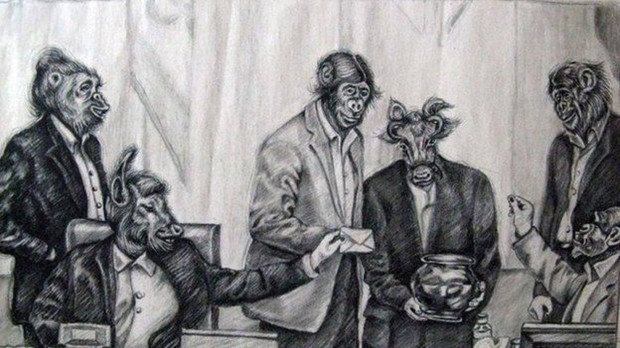

Atena Farghadani, 28, was sentenced to 12 years in prison for drawing a picture of Iran’s parliament as animals and posting it to Facebook. Her precise charge was, “insulting members of parliament through paintings” and “spreading propaganda against the system” (Facebook.)

In the midst of negotiations and work towards reconciliation with the west led by moderate president Hassan Rouhani, these arrests at first appear counterintuitive. However, the country’s judiciary is controlled entirely by its true head of state, the theocracy’s Supreme Leader. In the midst of the climate of reform, Supreme Leader Ali Khameni has used the arrests to prolifically solidify the position of the state and its brand of Sharia law.

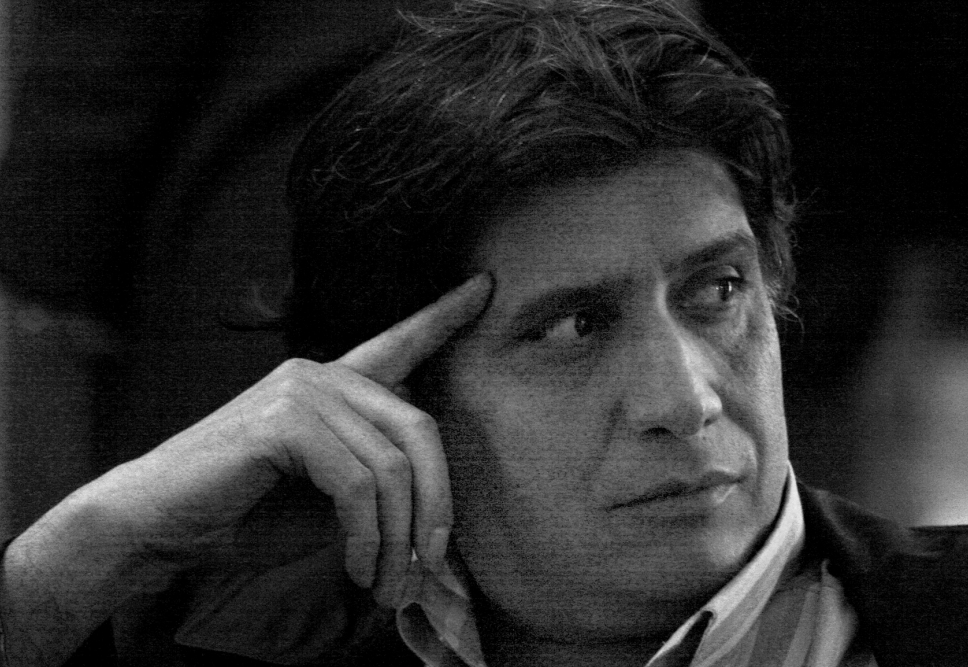

Filmmaker Mostafa Azizi. Azizi, who had lived in Toronto for five years, returned to Iran in January of 2015 to live with family including his ill and aging father under a program by the Rouhani administration which sought to bring about the return of Iranians living abroad. Azizi was put into solitary confinement at Tehran’s infamous Evin Prison on charges of “insulting the Supreme Leader”, “affronting the founder of the Islamic revolution”, “propagandizing against the regime”, and “conspiracy against the regime and public order.”

“He went back to live his life as promised by the images of change and moderation. He had moved back, given up his home in Canada, and was there for good, and was very happy to see his sick father. To this day what he wants is to live in Iran,” said Mostafa Azizi’s son Arash. The artist was sentenced to eight years in prison for his Facebook posts (Wikimedia Commons.)

Azizi, described by a member of the Persian culture center in Toronto where he volunteered as “a very active guy, with a huge passion for making sure that the voice of other less fortunate people was heard,” was given the sentence based on posts he made to Facebook. He was deemed to have “acted against national security, spread propaganda against the establishment, insulted the sacred, and insulted the heads of the Islamic Republic” by the country’s judiciary.

The clash between the judiciary and the executive branch has made people like Azizi into the victims of the power politics of a country at a crossroads.

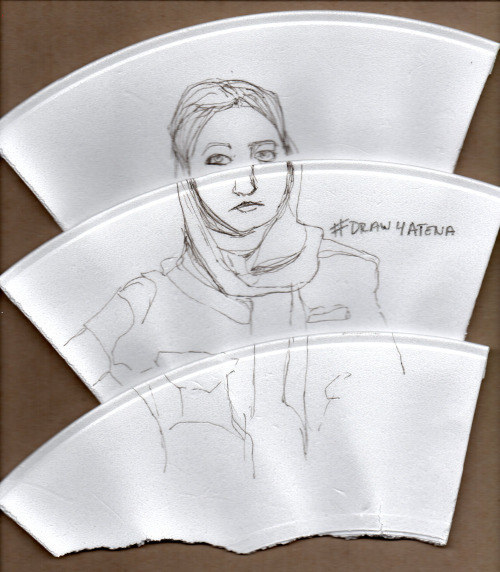

The 28-year-old artist Atena Farghadani is pictured in January, speaking out online after a temporary release in November. After the video was posted online, she was rearrested and brought back to Evin Prison (Youtube.)

Yet another casualty of this power struggle is the artist Atena Farghadani. In protest of a law restricting birth control and divorce, she drew a picture of her country’s parliament as monkeys and cows (see above.)

In response to sharing her cartoon on Facebook (officially labeled as “insulting members of parliament through paintings” and “spreading propaganda against the system”) Farghadani was blindfolded and taken to Evin Prison.

In prison, she began to draw on paper cups taken from the facility’s bathrooms.

The #Draw4Atena campaign has helped to bring widespread attention to Farghadani’s case (Sunny Leete / Tumblr.)

In prison, Farghadani went on hunger strike and suffered a heart attack. Further concerns for her health have helped to drive the push for an appeal of her case which will be heard later this month. This appeal is to come before the country’s Revolutionary Court, which falls accountable to the Supreme Leader. The Revolutionary Court’s rulings are final and cannot be appealed.

President Rouhani, when he was elected in 2013, was hoped to be a change in favor of moderation by much of the Islamic Republic’s population. And though he cannot officially pardon the activists or influence the courts, Rouhani has the ability to speak about them in public, an opportunity which he has often not availed himself of. Many critics of the new president’s human rights record have suggested that his eagerness to resolve the nuclear issue has led him to fall in line with the Supreme Leader’s domestic agenda. And the human cost of this concession cannot be understated. Under the judiciary’s régime of ruthless punishment for peaceful expression of dissent, even one’s choice in music can lead to years behind bars.

Atena Daemi, sentenced to seven years in prison for “insulting the Supreme Leader and the sacred” by having protest songs on her phone (International Campaign for Human Rights in Iran.)

In addition to the charge of “assembly and collusion against national security” for her Facebook post opposing forced hijab, activist Atena Daemi (who herself chooses to wear hijab) was given seven years in prison for having the protest songs of rapper Shahin Najafi on her phone.

Najafi, whose music addresses subjects such as poverty, drug addiction, and political executions, fled Iran for Germany but remains immensely popular in his home country’s underground scene.

Going forward, should President Rouhani continue not to take a stance in support of peaceful and free expression in his country, many Iranians see mass public protest as the most powerful option for freeing these prisoners of conscience.

“It has been proven many times that the regime will bow to pressure,” said Iranian exile and Washington, D.C. political cartoonist Nik Kowsar. “And if many human rights defenders remain in prison, I blame those governments that want to have business with Tehran, without bringing up [human rights cases.]”

For the moment, Iranians looking for the right to freedom of expression at home continue to look to the work of Azizi, Farghadani, Najafi, and other activist-artists, and for the moment, extremely harsh suppression of those rights and retributions for speaking out continue.