Iran’s most famous living artist, Parviz Tanavoli, has had his passport confiscated by authorities without explanation. The confiscation came a day before a Saturday exhibition in London. The dual Iranian-Canadian citizen has received no information from the passport agency, and it is unclear when he will be permitted to leave the country again.

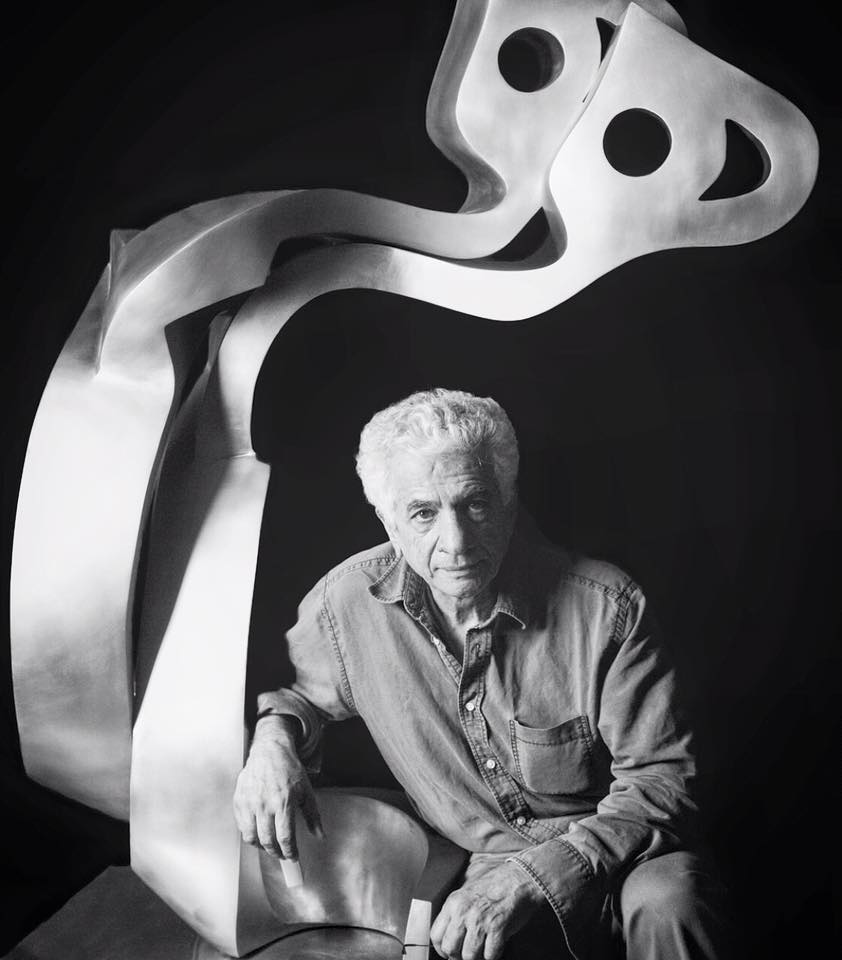

Iranian sculptor, collector, and historian Parviz Tanavoli poses in front of his work (Facebook).

Tanavoli was about to leave for an event at the British Museum for his new book European Women in Persian Houses when border officials at Tehran’s international airport confiscated his passport. After spending the entire day at the passport agency, he was given no reason for the government’s actions.

The book, published by I.B. Tauris under their gender studies branch, makes no political stand, instead focusing on the perception of western women in 19th century Persia.

“In a world where women were rarely seen in public and, even then, were heavily veiled, the notion of European women dressed in – by Iranian standards – elegant and revealing clothing must have sparked much curiosity and some titillation among well-to-do merchants and aristocrats…” explains the book’s abstract. Tanavoli studied images of European women which were a common feature in the interior design of affluent houses in the 19th century.

“I have no idea why they did it… I’m not a political person, I’m merely an artist.”

Parviz Tanavoli rose to prominence in Iran’s pop art movement of the 1960s and 70s. In 1971 he was commissioned by the country’s queen to create a sculpture for the Shah’s palace. Tanavoli’s finished work was a rendition of the word “heech,” Persian for “nothing.”

Parviz Tanavoli’s signature work “Heech” (“Nothing”) was featured in Iran’s royal palace (Tara Gallery).

Tanavoli recalled writing to the Shah in a panic that the work was not a critique of his rule, and that all meaning was personal to him. The Shah was satisfied, and his work remained.

His 1975 work “The Wall (Oh Persepolis)” is the highest-selling piece in the history of the Middle East, selling for over $2.8 million USD.

In addition to being an sculptor and art historian, Tanavoli is a collector. He has the largest collection of tribal artifacts in Iran, and plans to run his home as a private museum.

“He is not just an artist, he is a real historian of Iran and has systematically over the years published books about Persian carpets, amulets and other objects,” British Museum curator Venetia Porter told The Guardian. “This is what’s extraordinary about him: his deep love of Iranian culture, everything he does, all his art stems out of that.”

That plan to run his home as a museum has led to some trouble with Iranian officials in the past. He originally sold the home in Niavaran, an affluent district of Tehran, to the city on the condition that it become a museum. However, a sudden change in cultural policies saw the museum forcibly closed. Tanavoli, seeing the deal as broken, went back to his home to convert it into a museum that he would run. This led to an infamous 2014 police raid in which millions of dollars of sculptures were damaged.

Another sudden reversal in policy could be to blame for this event.

In 2016, Iran’s authorities have appeared confused in their treatment of art. In the past three months, two artist prisoners of conscience were freed, while three others began prison sentences for art. The work that is deemed acceptable my the state is increasingly arbitrary, and a book focusing on the portrayal of western women has proven to be a sensitive topic.

“I have no idea why they did it,” Tanavoli said. “I have not done anything wrong. I spent the whole day at the passport office but no one told me anything, nor did anyone at the airport.”

“I’m not a political person, I’m merely an artist,” he added.

Parviz Tanavoli usually splits his year between Tehran and Vancouver, Canada. It is unclear when the 79-year-old will be able to return to his family in North America.